How much does benefit abatement influence labour supply?

A common refrain when talking about unemployment benefits is the Iron Triangle of Welfare.

If we are only going to spend a fixed amount on welfare payments, then there is a trade-off between the size of the payment and the incentive to work – where the incentive to work is captured by how much of their new found labour earnings they get to keep. It is even a common point that I make when I’m off lecturing on the topic.

But what if I told you that empirical evidence suggests unemployment benefit recipients who are working don’t appear very responsive to what are essentially huge (50 percentage point) increases in their tax rate?

Well that is indeed what I find here, as discussed by the AFR here.

What does this mean? A number of things so lets have a chat.

Financial disincentives to work

When it comes to the Iron Triangle the “incentive to work” is about these fellas:

Note: Quick heads up that the above numbers are a bit buggy and based on unfinished code – and based on “old” payment rates in this alpha version of a tool here. But the pic is useful for talking concepts.

How do I read these without going through this excessively long blog post? The effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) noted here tells us that, if someone worked for an extra hour they’d give back this percentage of their hourly earnings to government – through taxes and reductions in their benefit.

The effective average tax rate (EATR) tells us that, if someone decided to work at a given hours level, they would give that percentage of their gross earnings back to government.

That is where this line comes from:

Currently, a single Australian working part time on the minimum wage at a department store will pay a higher effective tax rate (including both tax and the loss of benefit income) than someone earning in the low six figures at a large investment bank.

This is due to benefit abatement – in order to “keep the scheme cheap” we essentially ramp up the tax rate faced by those who are on the benefit.

Now that feels sort of BS, but one thing we need to remember is that these beneficiaries are still net recipients of financial support (or in other words they receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes).

So if our view was ONLY that the benefit should provide a minimum standard for people to live on, and we should aim to make this scheme as cheap as possible, we may design a scheme that has very high abatement – and therefore very high EMTRs and EATRs.

The trade-off given this poverty allieviation target is then behavioural responses – do people adjust how much they work because of this sharp abatement. And this is the area we want to build a bit of understanding about.

EMTRs and the intensive margin

Often our focus is on very high EMTRs and how that may lead people to restrict how much they work to stay on the benefit, or maximise government support.

This is what we term the intensive margin response – given you are working some hours, what is your incentive to work another one?

Based on fairly standard techniques we can look at bunching in taxable income data to get an idea of how much individuals manipulate their earnings to avoid paying a higher marginal tax rate. We can see that nice and clearly with our buddies “high income self-employed Aussies” right here:

Look at that spike in response to an 8 percentage point increase in the tax rate! Now such a spike can be the result of a bunch of things, actively adjusting who receives the earnings, when you receive the earnings, rounding bias in reporting an income amount, and a decision to change behaviour (such as work less) in order to earn that amount.

Self-employed people have the most ability to do this, but you do see these types of spikes occur all across the income distribution – including for low income earners at their tax brackets.

So what about benefit recipients when faced with the abatement rate going up by 50 percentage points – that is a big tax change, so it should be pretty wild right?

Na.

On this basis it doesn’t look like there is much of an “intensive margin” response by those on benefits. Similar non-responses show up across a variety of periods and also at the second threshold – while responses are quite typical at tax thresholds in Australia.

So tapering is all good right – as long as we are morally comfortable with these high tax rates on this group (which will still be negative tax rates when we think about it in terms of “redistribution”) no behaviour no problems?

Other margins: Mutual obligations and participation

Participation

Not so fast. Lets start with the elephant in the room – what about the 75-80% of JobSeekers who aren’t working? There is the reason the micro note starts with a clear definition of which margin we are looking at – because the response of these individuals also matters, and isn’t included.

Pushing up the income free zone to around $300 would provide a lump sum to everyone who is on the benefit and earning above that amount of $75. It would also pull a few higher low income earners onto the payment. But most importantly, it would reduce the EATR for a minimum wage worker who want to work part time in this range by around 8%.

The potential to bring in an extra $75 a fortnight if you can find a job that pays anywhere between $300 and $1,000 a fortnight could have implications for people’s willingness to participate – and it could be that any labour supply action you see occurs there. This is an important reflection as noted here:

A ‘large’ extensive elasticity at low earnings can ‘turn around’ the impact of declining social weights implying a higher transfer to low earning workers than those out of work, in turn providing an argument for lower tax rates at low earnings and a role for earned income tax credits.

Blundell, Bozio, Laroque (2011)

Information and barriers

For those working there is a separate approach that captures that there may be informational frictions, or other frictions that lead to bunching “shifting the counterfactual”. Chetty etal 2013 discusses this in great detail – strong recommend. There are two ways this can chip in:

- The change in bunching may occur at “salient balances”,

- The broad density associated with the distribution may move – rather than spike.

For a long time I believed the result had to be one of those two – with the difficult thing defining the “counterfactual group” that could be used to construct it. Lets just say that this “extensive-intensive” margin just didn’t end up changing anything – but is something I’m passionate to keep testing results against it.

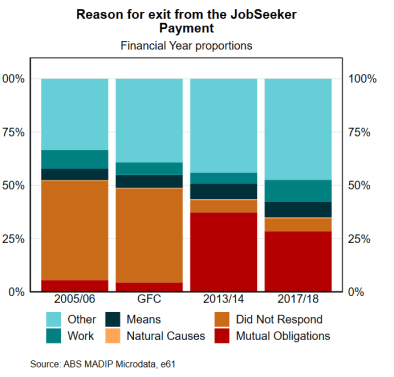

Regulatory barriers – mutual obligations

However, there is an important reason why the limited intensive margin response may show up in any extensive margin work – the heavy importance of mutual obligations.

The micro note focuses pretty heavily on mutual obligations as a concern.

The Australian benefit system has surprised me with the sheer amount of conditions individuals and supposed to meet to receive payment. Specifically, significant job search requirements – and the threat of payment removal that is credible – make undertaking part time work to avoid these obligations attractive in of themselves. Part-time work requirements to remove mutual obligations vary, and short amounts of work can be mixed with other requirements in order to maintain benefit eligibility.

If this is the case, then individuals will simply be taking up the job offers available – the lack of bunching behaviour makes sense. However, if it is mutual obligations driving this “non-response” on the intensive margin, then it should show up on the extensive margin as well – given the risk of losing your benefit if you don’t take up marginal work, those who are particularly responsive to financial incentives may have already jumped into work to insure themselves against this loss.

The fact that benefit thresholds don’t show bunching while the tax thresholds do – even at the low end – does indicate that is a systematic difference in the choices made. Although it is common for people to make comments about rationality and attentiveness I call this out in the note – it is more plausible this is about the choice set available to people and the genuine ETRs they face when making these choices.

Mutual obligations are a big part of this. And their existence will change how responsive individuals will be to a change in headline financial incentive measures.

So the potential for people to “move into” work from out of work remains a key margin to understand – but the note is indicating that the stark non-bunching in combination with the mutual obligations system suggests that pure financial incentives might not be enough, given the importance of regulation and mutual obligations for low income earners.

So this gives two key research directions for these labour supply responses – extensive margin responses, and the efficacy of mutual obligations. Let me get back to you on that 😉